Each year, politicians and government officials spend a large portion of their time fighting for just a small piece of the national budget to benefit towards their goals and interests as representatives of the community. In small towns like Amatlán, a town representative may be fighting towards a small education budget to benefit the remodeling of primary school. Or in larger cities like Cuernavaca, a city mayor may be interested in a larger budget from the national funds to increase teacher salaries or to increase extracurricular activities in public schools. But due to Mexico’s history and reputation of governmental corruption, it begs the question of exactly how much of this money is actually benefiting the systems it’s given specifically for.

In April 2017, fugitive former governor of Mexico’s Veracruz state, Javier Duarte, was arrested in Guatemala by Interpol for accusations just a year before of organized crime and money laundering (Associated Press). It was estimated at least $645 million Mexican pesos were siphoned off by the governor during his time in office from 2010 to 2016 (“Fugitive”). Under Duarte’s administration, Veracruz also interestingly became “the most dangerous region of the country for journalists,” with 17 killed during his term. Due to the accusations, Duarte was suspended from his party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (El Partido Revolucionario Institucional), also commonly known as PRI, which governed Mexico for the past seventy years and is the party of the current President, Enrique Peña Nieto. Research conducted by María Amparo Casar, the Executive President of the activist group Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity, founded that “of 42 governors suspected of corruption since 2000, only 17 were investigated” and “before the most recent arrests, only three were in jail” (Malkin). Another great example is Tomás Yárrington, the former governor of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas arrested in Italy just weeks before Duarte’s arrest. Yárrington was arrested on charges from Mexico and the United States for money laundering and organized crime where he accepted bribes from drug cartels in exchange for free reign in his state.

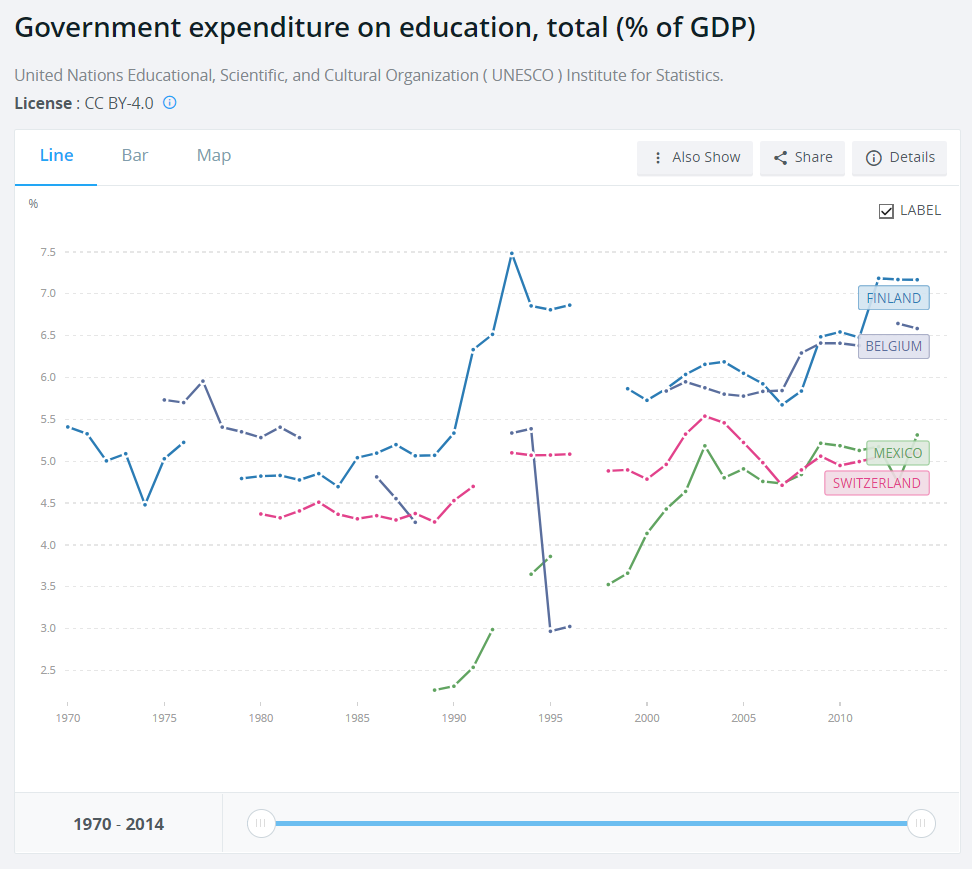

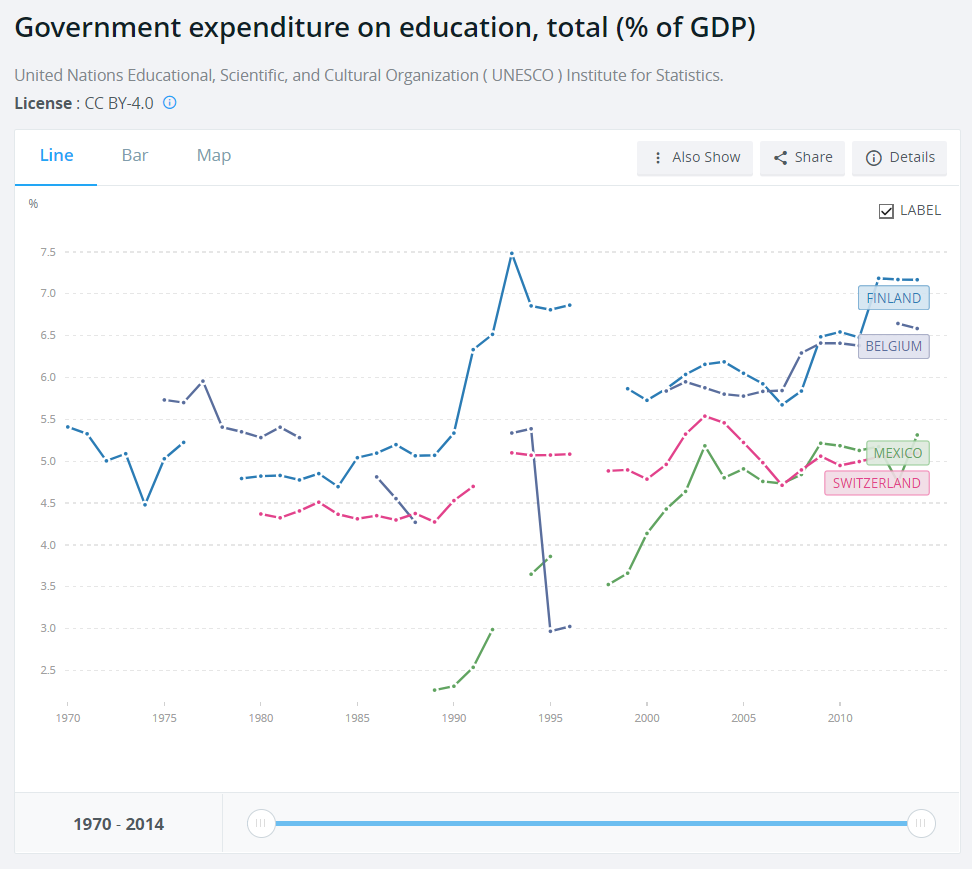

According to the World Bank, Mexico has gradually increased its spending on education between 1989 to 2014 with a low point of 2.265% of the GDP invested in education in 1989, and a high peak at 2014 with 5.313%. That’s roughly about $0.24 MXN trillion pesos of $4.50 trillion MXN pesos ($18.23 billion USD of $343.11 billion USD) (Reuters Staff). In comparison with some well-known countries for education, Finland, Belgium, and Switzerland are holding title as Independent’s top three in the world for 2016 (Willams-Grut). In 2014, Finland’s government had a total expenditure of 7.168% of its GDP on education; Belgium with 6.585%; and Switzerland with 5.096%, just slightly below Mexico. A common pattern here with the exception of Switzerland is a somewhat linear relationship between government spending and quality of education – “the more invested in education, the better it’s quality.”

Mexico’s education budget percentage

Wait, Mexico has a close percentage to other countries, why is its education quality not as ‘good’? Well, it begs the question of exactly just how much is actually being invested into the schools, resources, and programs for educational growth? A study conducted by John W. Miller, president of Central Connecticut State University in Connecticut, analyzed trends in literate behavior and the literacy rates of over 60 countries. Among the top ten were Nordic countries (in consecutive order from first place to tenth) Finland, Norway, Iceland, Denmark Sweden, Switzerland, United States, Germany, Latvia, and the Netherlands. And among the bottom ten from 50th place to 60th consecutively are Turkey, Georgia, Tunisia, Malaysia, Albania, Panama, South Africa, Colombia, Morocco, Thailand, Indonesia and Botswana. Mexico sits roughly in the middle at country #38.

Works Cited

Associated Press. “Fugitive Mexican Governor Javier Duarte Arrested for Alleged Corruption.” Www.telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited, 16 Apr. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2018.

“Fugitive Mexican Governor Javier Duarte Arrested in Guatemala.” BBC. BBC, 16 Apr. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2018.

“Government Expenditure on Education, Total (% of GDP).” World Bank. The World Bank Group, n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

Malkin, Elisabeth. “Corruption at a Level of Audacity ‘Never Seen in Mexico’.” New York Times. The New York Times Company, 19 Apr. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2018.

Reuters Staff. “Mexican Congress Completes 2014 Budget Approval.” Reuters. Reuters, 14 Nov. 2014. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

Strauss, Valerie. “Most Literate Nation in the World? Not the U.S., New Ranking Says.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post, 8 Mar. 2016. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

United States of America. U.S. Department of Education. Nces.ed.gov. National Center for Education Statistics, 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2018.

Willams-Grut, Oscar. “The 11 Best School Systems in the World.” Independent. Independent Digital News & MediaIndependent Digital News & Media, 18 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.